FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

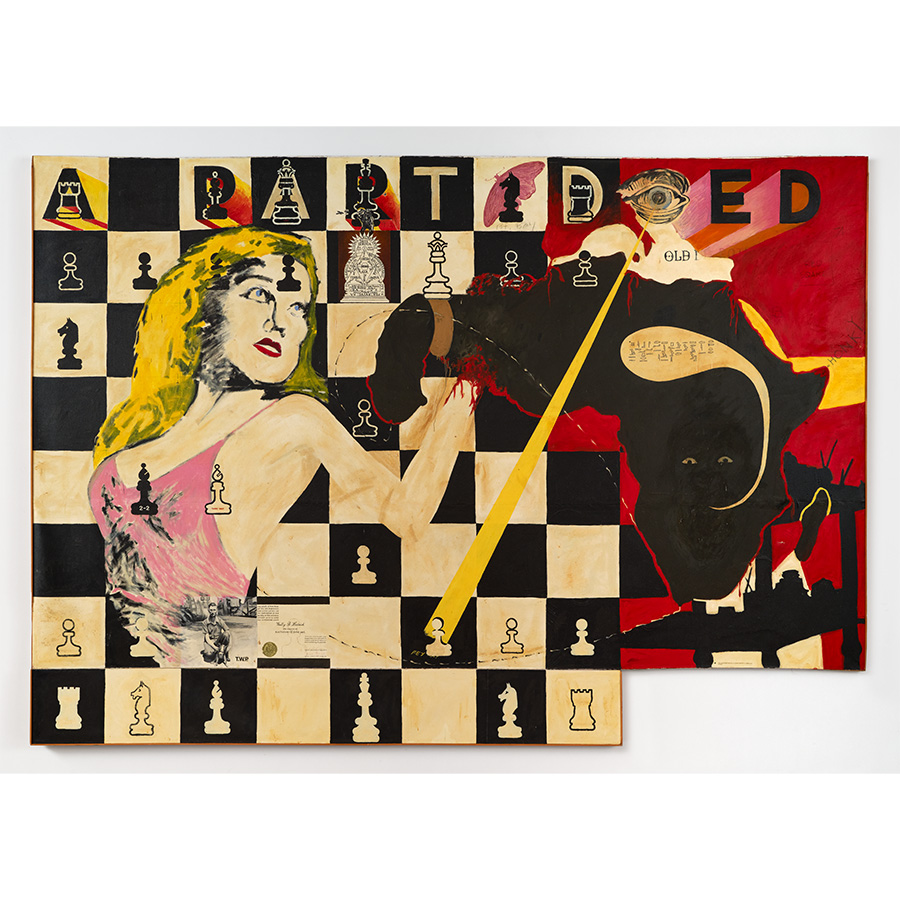

WALLY HEDRICK: SEX POLITICS RELIGION

FEBRUARY 14 – APRIL 4, 2026.

WEDNESDAY - SATURDAY, 11-6 PM.

OPENING RECEPTIONS: FEBRUARY 14, 2026

PARKER GALLERY | 3-6PM

THE BOX | 5-8PM

The Box and Parker Gallery are proud to present a retrospective of Wally Hedrick (b. 1928 Pasadena, CA–d. 2003 Bodega Bay, CA). This marks the first retrospective in 40 years and the first in the artist's hometown. To coincide with the exhibition, the galleries will host a Hedrick symposium at The Box on March 28, 2026.

Wally Hedrick (1928-2003) flatly rejected any consistent aesthetic: “I have contempt for style.”[1] For him, style was not a matter of personal expression, it was material used in service of whatever idea motivated the project at hand. Hedrick bounced from welded assemblage junk sculpture to Bauhausian abstraction to black monochromes to gestural figuration to graphic signage to pictographic diagrams to near-photorealism. And not in any linear progression: “There’s no continuity in my work at all. I don’t paint from one painting to the next because I’m not interested in development painting. I’m interested in ideas.”[2]

If anything, the eccentric variability and range of his paintings and sculptures became his work’s defining trait. He thought of himself as “a great improviser,”[3] in the manner of the Bay Area jazz musicians he admired and played with in bands back in the day. Running against the grain of, say, identity politics, everything about him scorned any cookie-cutter, prefab, categorical identity. Hedrick contributed as much in the radical way he went about being an artist as anything. Which gets at some of his other defining traits—his irrepressible irreverence, his fierce independence, and his “fuck ‘em” attitude that rebuffed authority, propriety, status, and conventionality of all kinds. His very existence stands as a monument, if not a relic.

Growing up in Pasadena, where he was influenced early on by Paul Klee, Constructivism, and Von Dutch hot rods, Hedrick came into his own when he moved to San Francisco—first in 1947 and then again in 1952, after serving in the Korean War. He attended the California School of Fine Art (later renamed San Francisco Art Institute) on the GI Bill, under faculty Clifford Still, David Park, and Elmer Bischoff. Deeply enmeshed in the creative community, he was at the beating heart of the jazz, Beat, and Funk scenes that brought together musicians, poets, dancers, and artists. With close friends Deborah Remington, David Simpson, John Allen Ryan, and Hayward King (all of whom moved north together from Pasadena) and poet Jack Spicer, Hedrick co-founded the legendary 6 Gallery, at 3119 Fillmore, which became a crucial gathering spot and hotbed of radical, experimental art where the seeds of what became known as “Happenings” were sown. The gallery’s opening event—a fundraiser at which Allan Kaprow was present—culminated in the spontaneous blowtorching of a piano, for example. Or, most famously, Allen Ginsberg debuted “Howl” there, reading from the toilet to a crowd that included Jack Kerouac. Hedrick improvised light shows, repurposing common things like cheesegraters, as accompaniment to poetry readings with progressive jazz in the background. Far out.

Though often associated with the outrageousness of Funk art, he didn’t identify as such, pointing instead to his good friends Joan Brown and Manuel Neri and his then-wife Jay DeFeo as quintessentially, authentically funk. His intimate relationship to DeFeo surfaces in the title and image of a painting like J. Me Et Cat (1954) and the geometric, concentric compositions of Love Feel (1957) and Heroic Image (1959). Both Hedrick and DeFeo were included in the landmark “Sixteen Americans” exhibition at MoMA in 1959, alongside canonical figures like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, and Ellsworth Kelly. They did not go to New York for the opening. Four years earlier, at age 27, Hedrick had his first museum solo show at the de Young Museum. And just over a decade later, retreating from his early successes, he decamped from San Francisco to Marin in 1970, ultimately settling in Bodega Bay where he remained, and continued to make art, until the end. He had long thought of himself as operating underground.

Years before leaving the city, Hedrick had already entered into an extended withdrawal where he stopped showing his paintings and resigned (or was fired) from his teaching position in protest of the Vietnam War: “In ’63 I had decided that I would withdraw my services from almost everything. …I was going to stop the war by not letting anybody see my work.”[4] Leading up to that withdrawal, and with his own war experience still fresh, he started going dark as early as the mid-50s with a series of richly textured, black monochrome paintings conceived as powerful anti-war statements that have since proved evergreen over the years, canvases sometimes reworked and updated to address new conflicts. He was the first American artist to protest the Vietnam War. Reflecting on that critical gesture that continues to reverberate today, he noted wryly, “I don’t use black oil for no reason. …I’m a politician. I’m trying to make these paintings do what politicians should be doing.”[5] The black paintings grew and reached their apotheosis as America’s involvement in the Vietnam War reached its height, culminating in War Room (1967/1968/1971/2002), a square room construction over twelve feet across enclosed by enormous panels of black paintings facing inward, their canvas backs and stretcher bars facing out with a small hinged panel as a door on one side.

Away from the city, the scene, and his career, he survived off of Wally’s Fix-It Shop, repairing people’s junk—ever-spurred by poverty to scavenge in defiance of consumer culture and in alignment with the West Coast assemblage movement that had the strength of moral conviction. Often incorporating imagery from popular media and art history, his practice was driven by the engine of protest, a red-hot fire emanating foremost from his anti-war feeling, cut through with the acid of absurdity, black humor, ironic punning, nihilistic abandon, and libidinal desire. Throughout the decades, he returned repeatedly to sexual imagery and allusions as a parallel way to convey the visceral energy and spiritual tension of his liberatory pursuit. In its totality, Hedrick’s work argues, perhaps anachronistically now, for art as a volatile, risky pursuit with real life stakes, a way of thinking and being at odds with the conventions of our world. His art was a declaration of independence that appears increasingly distant today: “I don’t say that I’m free, but every increment of freedom is important to me. I decided a long time ago that I can’t be a nice, middle-class American and do what I want to do.”[6]

-- Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer